Index

- No victory points!

- The first try

- Transform your Home into a Spaceship!

- From big to small

- How much action is too much action

- The right mixture makes it

No victory points!

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away... Well, not quite. But quite a long time ago, in 2015 to be precise, we took the very first step on the long journey that eventually ended in the publication of Spaceship Unity. We, in this instance are: Jens Merkl and myself Ulrich Blum. Jens and I wanted to start a game project together. We had met a few years prior and seemed to have similar ideas about games. In our first meeting for this, we both came prepared with a few ideas that we pitched to each other, to see what excited both of us. There were a few interesting ideas from both of us, but somehow none of them really lit a fire in us. So we started discussing games in general and what we found was missing from the market, such as themes we thought were interesting but haven't been done to death yet. In that discussion we realized that so many times a new and exciting theme was just set dressing for mechanics. Not that that is necessarily bad, but we wanted something else than a game where in the end it's still about collecting victory points. What about a game where there are no victory points? Hmm. Now that was an interesting challenge.

The first try

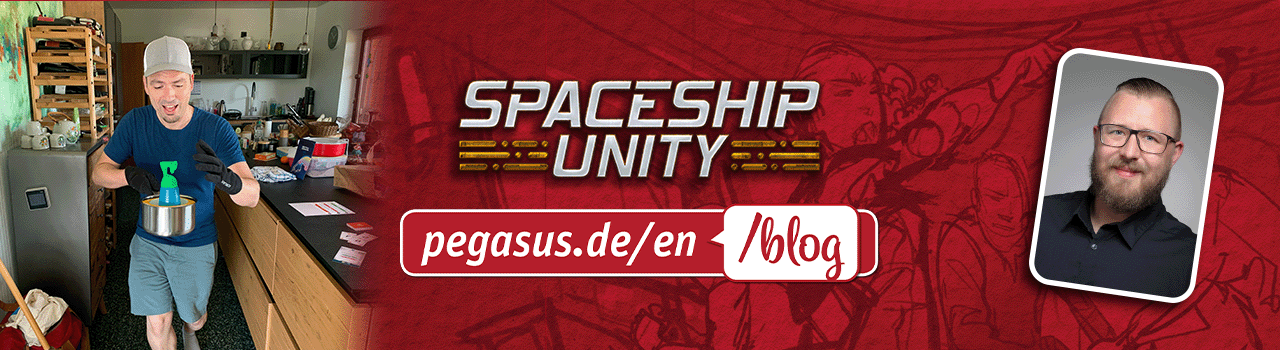

In the following weeks we collected ideas about which experiences we wanted the players to have that were challenging but beyond optimizing victory points. What we landed on was the type of Indiana Jones / MacGyver sort of adventure, where there is a series of mortal perils that need to be overcome with wit and resourcefulness. The game came together rather quickly. The basic idea was to deal with situations that were presented to you only with a picture. To overcome the situation players had all kinds of objects that were also just pictures. There was a little more to it, but that doesn't matter here. The only other thing to mention is, that the game was played in several rooms of the apartment you were playing in, to give a feeling of the changing locations of the Temple we were exploring.

We were quite happy with the game, so we arranged for this to be played with two editors we know at a gaming event. And let's just say they were not quite as excited about it as we were. They tore the thing to shreds in their feedback. We don't need to go into the details, the main point was: most of that feedback was totally justified. And then at some point the crucial sentence was said: "The only thing that I find interesting about this, is that we're not sitting at the table but use the whole space."

We went home and it was clear: this game was not going to go anywhere. So, we dumped it. Not a nice thing to do after you have put several weeks of work into something, but unfortunately sometimes it's what you need to do. Instead we basically started over and asked ourselves: So, using the whole space and moving around. What can we do with that?

Transform your Home into a Spaceship!

A whole lot, it turned out! Once we established, that the whole living space was potentially used for this game, we realized we could also use all the things a "normal" apartment usually contains. A chair, a table, cutlery, books, clothing, etc. Could we use them to solve situations presented to the players just like in the first game? And what is the situation the players are living through? Can we transform the apartment into something more exciting? That's when the most important realization hit: When you watch younger kids playing, they can use almost everything as a toy. To them it's not a shoe stomping on paper clips, it's Godzilla crushing the fleeing citizens of Hong Kong. If we could manage to tap into that kind of playful energy, we would really have something special!

We landed on a spaceship as a setting. It lends itself perfectly for a setting in which there are all kinds of "machines" to be operated. Those machines can be represented by actual things in the apartment. It's also a great setting for a team working together. And most of all: It's exciting! So that was settled. But what would we do mechanically on that spaceship? How do we get players to use socks for shooting lasers?

From big to small

We started with five or six systems with their own little minigame that would involve everyday objects. We realized, it would be hard to remember the different minigames, so we put a reference card for all of them next to the object they were using. We tested that between the two of us with a tiny little adventure as a stand-in for an actual story. It contained a few cards telling the story and what to do on the systems of the spaceship. The idea was to test the systems and care about how to tell the story later.

It worked ok, but the more obvious thing was staring right at us: Instead of reference cards for the systems, why not just write the full rules for those minigames on them and make reading them part of the game. On the negative side that would mean the minigames couldn't be very complex. But on the positive it meant we could have as many of them as we wanted, because players wouldn't have to learn them in advance. That was a trade we were more than willing to take.

So we now knew how the systems of our spaceship would be handled. Obviously, we would have to come up with a ton of minigames, but for now we could work with a few and figure out when and why they would be used. It was obvious that there should be some kind of story that would create problems for the players to overcome and thereby motivating the use of the spaceship's systems. We played around with different solutions. Presenting players with a situation and having them figure out what to do themselves was theoretically interesting but ended up being more of a puzzle than a frenzied space battle. After several iterations we landed back on our very first solution: The few cards we used as a stand-in for the story to test the systems. They would just tell you what to do and at the same time could hold a few sentences to advance the story. Just being told what to do didn't sound very exciting in theory, but the players already had so much to figure out (where is the system? How do I use it?) that this was actually the best solution.

How much action is too much action

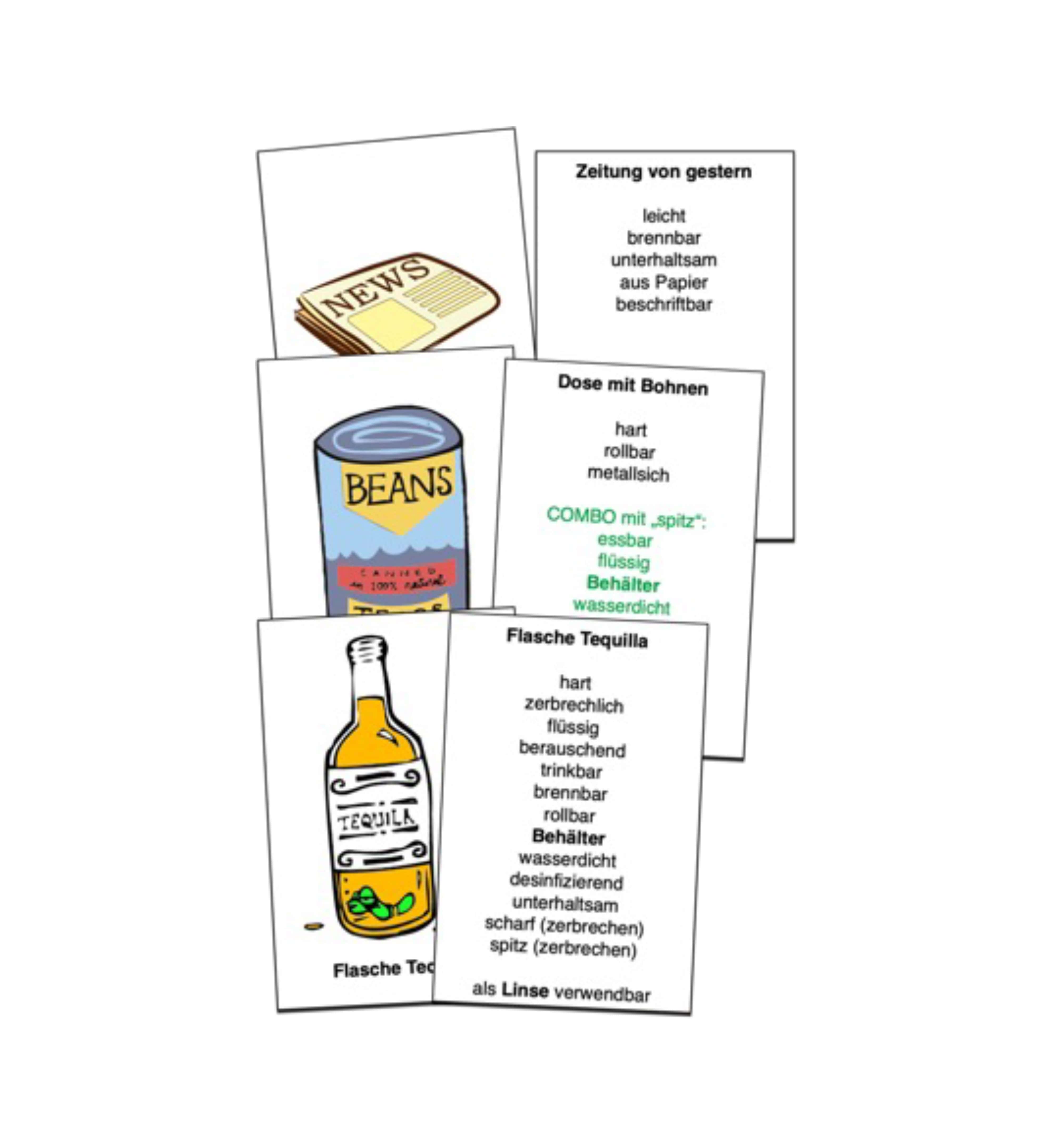

There was an element of time pressure in the game from the very start. At first we just had a time limit for the whole thing. Something like: you have 10 minutes to get through this stack of cards and do everything on there. While that was definitely the right direction, we wanted to break that up into smaller units. And so the life support track was born. A series of spaces onto which you put a sand timer. That sand timer must be running all the time. So each time just before it runs out you need to turn it over. When you turn it over you advance it to the next space. If you reach the last space, you lose. And if the sand runs out because you forgot about it you also lose. And that element worked very well from the start and is almost unchanged in the final game.

And now we could place symbols onto the spaces of that life support track, that would trigger special things when the timer would reach that space. How about malfunctions? That sounds like fun. Nothing more wonderful than your laser malfunctioning in the middle of a space battle, right? The malfunctions were a blast. They did a good job of breaking up the scripted nature of the cards that told us what to do. Players could always eliminate malfunctions without a prompt from a card. Because you don't want a system to be down during the moment you're supposed to use it.

We felt we had something quite good at that point. And a few tests with people other than ourselves proved that. But it became very apparent that no one wanted to be under time pressure for an hour. 15 minutes was the longest most people were willing to do that at a time. So we had the choice of either making this a 15 minute game or come up with a solution. Making it a very short game was not what we had in mind. We wanted an epic space opera. That experience was not going to happen in 15 minutes. We needed another mechanism to break up the frenzy and give players a moment to catch their breath. Just as a good sci-fi movie has action sequences and quiet moments. But wouldn't that mean creating a completely separate game? Was there a way to use some of the elements from what we created so far, without time pressure?

The right mixture makes it

This was a little harder than the creation of the action sequences that we already had. The Problem was that the challenge up to this point revolved completely around time. If the time pressure was removed from the game it became banal. It would be a mere sequence of tasks to be performed without any player agency. The whole point was to be quick. After a while we were able to crack that nut though. What we needed was another set of minigames for the systems. The ones we already had mostly focused on tasks that would feel like the things the system would do in the story. For example, the Shield generator is activated by lowering the blinds, lasers are fired by throwing socks around and shouting "pew pew pew" etc. What we needed for the not timed sections were minigames that were a challenge in and of themselves. Things that could go wrong. For example, recalibrating the laser by throwing a sock in the air and catching it behind your back. That way each fail on one of these minigames would move the timer on the life support track one space forward, instead of actual time passing. We could keep the main mechanism of the life support track as the unifying element between the two game states. The cards with the story would again tell us exactly what to do but each one of those tasks was now a challenge.

At this point we had the main elements of the game system all there. And tests were very promising. If this was a "normal" game we could start looking for a publisher and clean up the little kinks along the way. But this was not that kind of game. We knew how to tell the story now. But what kind of story? In what structure?

Ulrich Blum

What, this is the end? Of course not! The journey is just beginning. In the second part of the Spaceship Unity Designer Diary, Ulrich tells you more about the game development and the creation of the epic sci-fi story of Spaceship Unity - or how an epic space opera is made.

Questions, comments, feedback? Share your thoughts with us at blog@pegasus.de.